Ever regret about how you dealt with anger in the past? We all have. In this blog, I’d like to share with you one thing I have learned from decades of research on emotion, that may be helpful for you.

Ever regret about how you dealt with anger in the past? We all have. In this blog, I’d like to share with you one thing I have learned from decades of research on emotion, that may be helpful for you.

What is anger?

When we think about potentially destructive emotions, we often think about anger. And for good reason.

Anger is probably the most common emotion that we have that leads to feelings of regret later. Now, I don’t believe anger is inherently a “bad” emotion; getting angry can result in some good in our lives and in society. Anger, and all other basic emotions, exist for a reason.

In our evolutionary history, being angry (and disgusted and afraid and sad, etc.) was functional for us. That is, anger, as all other basic emotions, helped us deal with problems in our lives and in our environments in order to survive. In our evolutionary past, emotions like anger were important in order to deal with many life struggles. All our emotions allowed us to handle incredibly difficult events that required us to think with minimal conscious awareness.

Emotions have helped us deal with birth, death, finding food, fighting for mates and resources, and everything else required for living for eons. Anger, and all other emotions, have helped us deal with all these problems of living. Put another way, if we didn’t have anger (and the other emotions), we wouldn’t be here in the first place.

Or more precisely, those individuals that did not have emotion systems in them were selected out of existence by nature, as part of natural selection.

Anger and Regret

But sometimes our anger gets the best of us, and we become angry and later regret having become angry.

But sometimes our anger gets the best of us, and we become angry and later regret having become angry.

Here are three reasons why we later regret having become angry:

- Anger was an inappropriate reaction to the situation.

- Anger was the appropriate reaction to the situation, but we expressed it too intensely.

- Anger was the appropriate reaction to the situation, but we expressed our anger in a way that harmed someone else.

I’d like to focus on that last reason why we may regret our anger. That last one – expressing anger in ways that hurt or harm others – is particularly problematic because it often (not always) happens unnecessarily. This may be true of not only loved ones, family and friends, but also of strangers.

You only hurt the ones you love?

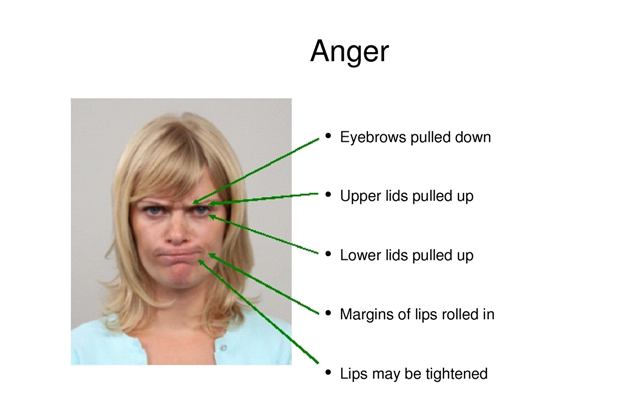

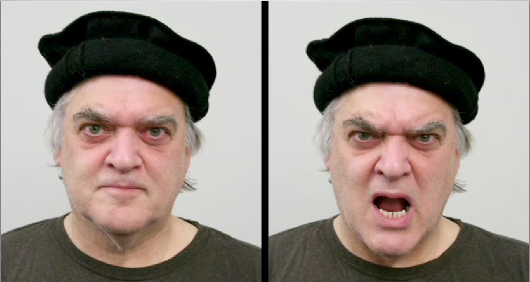

Here’s why this occurs. When we are emotional, one thing that occurs is cognitive gating. When triggered, emotions channel our senses, perceptions, and minds to let in certain things and block out others. In the case of anger, when we are angry, our sensory system gets very sensitive to signals of anger in our environment.

This makes perfect sense, because one thing the emotion of anger does is to recruit an organized system of bodily responses that helps prepare us to fight.

In doing so, our minds are unconsciously on the lookout for signs of anger in others, because we want to know who else is ready to fight in order to be aware of potential threats. So we become hypervigilant to other signs of anger in others.

But what does that do to an interaction?

That means that when we get angry and express that anger, we are hypervigilant to signs of anger. Others can pick up our signals of anger themselves, easily and unconsciously. Those perceptions, in turn, trigger anger in them, who then express that anger themselves.

That means that when we get angry and express that anger, we are hypervigilant to signs of anger. Others can pick up our signals of anger themselves, easily and unconsciously. Those perceptions, in turn, trigger anger in them, who then express that anger themselves.

We, who are already hypervigilant to anger signals, pick up those signals and this further fuels our anger, and we express more. And then they pick up those angry signals, get even more angry, and express even more.

This anger exchange cycle continues really quickly so that even after a few short seconds, people are arguing, and sometimes fighting, because they are both angry, while the original issue that started everything in the first place has been forgotten.

What to do?

Fortunately, research on what are known as emotion antecedents and appraisals can help in this regard. I was very lucky to be involved with this area of emotion research early in my career, working with some of the most well-known scientists on emotion appraisals and antecedents. Decades of emotion science has led to many appraisal theories of emotion, which are well accepted theories about how emotions are elicited.

Most scholars accept that emotions are triggered by some kind of appraisal process in the mind. That is, when an event occurs, our minds evaluate (appraise) the event. Some events trigger emotions, some don’t. How is that determined? That’s what appraisal theories do. They provide guidelines of what’s going on in our heads to trigger certain emotions.

Cross-cultural research on emotion antecedents and appraisals has shown that there are relatively few cultural differences in the specific types of events that trigger emotions in us. Of course when an event only occurs in one culture, it can’t trigger emotions in another. But by and large the same types of events can trigger emotions all around the world (which is very interesting in its own right). Unsurprisingly, many emotions are triggered in social situations in all cultures.

Most importantly, the research has suggested that basic emotions are associated with universal, psychological triggers that underlie event appraisals. That is, regardless of what the specific event is, there are certain elemental psychological themes that bring about emotions. And with basic emotions, the same elemental psychological themes trigger emotions all around the world. That’s an amazing thing, and provides another basis for understanding emotions all around us, despite cultural differences. It’s another reason why emotions are a universal language.

With anger, the universal psychological theme that triggers anger all over the world is…. (drum roll….)

Goal obstruction.

That is, anger is the emotion that is triggered when our goals are blocked or obstructed. This makes sense also, because when our goals are blocked, anger helps prepare our bodies to fight in order to removal those obstacles.

Obstructions are usually not people; they’re actions, or more precisely the results of actions.

If you get angry about how the tube of toothpaste is rolled, for instance, the obstruction is the way the toothpaste is rolled, not the person who rolled it. Thus, in a strict sense we should be thinking about how to deal with actions or their results when we become angry.

Anger Management

The problem is that when something occurs to trigger anger in us, we are quick to associate the obstruction with the person who did the action that resulted in the obstruction.

The problem is that when something occurs to trigger anger in us, we are quick to associate the obstruction with the person who did the action that resulted in the obstruction.

That is, we personalize the anger by blaming the person and not the action; we blame the person who rolled the toothpaste. But in doing so we are misplacing the actual trigger, because the anger trigger is the obstruction, not the person who caused the obstruction.

For example, when your spouse does something to irritate you (irritation is part of the anger family; see here for our blog on emotion families), we are quick to blame the person (spouse) when in fact we should be focusing on the obstruction itself (such as how to roll the tube of toothpaste).

Blaming the person would lead to our expressions of anger toward the person when in fact we could and should be directing our angry energy to the obstruction (how to come up with solutions to rolling a single tube of toothpaste), not the person. Or better yet, we might want to consider why the goal was so important to us in the first place, which may lead us down a different path altogether involving some interesting self-reflection.

Blaming people and not actions is how we can get into a destructive cycle of angry reactions towards others, like I discussed above.

If we can reframe our thinking to the obstruction and not the person, we can focus our discussion on solving the obstruction while maintaining relationships, not harming them.

How do you control anger outbursts? Of course, needing to know that one can reappraise the situation when you’re angry requires you to be aware that you’re angry in the first place. That’s all about emotion regulation.

For our tips on how to do so, check out our recent blog on our #1 tip to manage our emotions.

I would like to recibe more information about this topic